The Artful Dodger: Social Engineering, Pen-Testing, and a Toast to Robert Redford

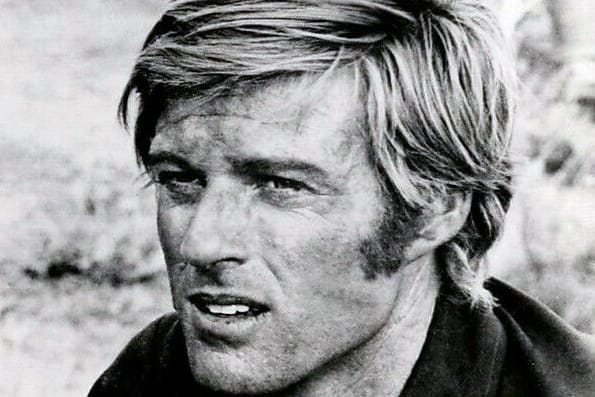

When the internet whispers “just patch the server,” it forgets the sensible little human who will prop the back door open with a smile. In the old caper film tradition, breaking into a place rarely required a sledgehammer; it required a line, a prop, perfect timing, and someone who believed you. That’s why Sneakers, the 1992 movie where Robert Redford leads a team of lovable misfits who test and break security for a living, still sits on the security curriculum like a charming, slightly illegal professor. The ritualised hotel scene, where a birthday cake and a bag of balloons substitute for a toolkit, is not just movie theatre; it’s a masterclass in human hacking. Robert Redford’s Martin Bishop charms, deflects, and convinces without breaking a sweat, and that combination of charisma and craft is worth studying by anyone who spends too much time talking to monitors and not enough time talking to people.

Redford’s death on 16 September 2025 invites a small cultural reckoning: among the legions mourning an actor and festival founder, there are also security nerds who owe him a debt for making the caper glamorous and making social engineering feel like an art form. The lesson isn’t “be a con man”; the lesson is that humans, like systems, have predictable behaviors, and those behaviors bend under pressure, distraction, and a really good story. If the younger generation of cybersecurity practitioners learn one thing from Bishop, let it be this: be human first, hacker second. That means read people, not just logs. That means attend a Meetup, listen to someone’s weekend anecdote, and learn what makes strangers pause and what makes them help. It’s easier to exploit someone you understand.

Social engineering in real life looks less cinematic and more mundane: a terse phone call pretending to be IT, a clipboard and a “vendor” badge, a follow-through on a trivial request that yields access. Penetration testers have institutionalised these techniques because they work. Ethical red teams combine phishing, vishing, tailgating, and old-fashioned awkwardness to measure how likely an organisation is to hand over keys. The point of a social test is not to expose a single gullible receptionist, it is to identify process gaps: where does policy stop, where does empathy begin, and where do attackers exploit the seam? Doing that well requires the same skills that made caper films fun, planning, roles, timing, and then documenting the fallout so the client can actually fix the thing.

The hotel scene in Sneakers works because it’s absurdly ordinary. Nobody picked a lock or brute-forced a cipher; they just carried a cake, looked confident, and relied on the fact that receptionists are paid to be polite, not paranoid. That’s the marrow of social engineering: the easiest way in is through the part of the system that wants to help you.

For penetration testers, that lesson is uncomfortable but essential. You can spend weeks rehearsing payloads, or you can spend ten minutes practising how to sound like you belong. The catch is that in real life you don’t get to play anarchist theatre. There’s paperwork, scope agreements, and lawyers who frown when you suggest dressing up as a singing telegram. The art isn’t in humiliating staff; it’s in showing the client that their strongest crypto still falls apart if Dave from front-desk waves you in because you looked trustworthy.

Defenders, meanwhile, can stop wringing their hands about “the human factor” as if it’s a virus to be eradicated. Humans are helpful; that’s not a bug, it’s the whole species. The trick is to give them scripts and processes that make suspicion feel natural. If your policy says “always verify IDs,” then make that socially easy to do. If your visitor log lives under a pile of takeaway menus, don’t be surprised when someone skips it. Security isn’t about lecturing people not to be kind; it’s about making kindness less exploitable.

In short: don’t obsess over teaching staff to smell a rat. Rats are sneaky by design. Instead, design the cage so the rat has to work harder. That’s what Bishop and his crew showed us with balloons and a birthday cake, and it’s still the sharpest lesson three decades later.

For the benefit of the young and the nerdy: charm can be learned, but it should be used responsibly. Redford’s smirk isn’t a contrivance; it’s a social tool that disarms and redirects. For practitioners who never learned small talk beyond “Have you tried turning it off and on again?”, take a note from caper craft. Learn to listen to a person’s priorities. Notice what they repeat. Ask one honest, curious question and then shut up. You’ll be surprised how quickly someone gives you the shape of their day, and the policy gaps inside it. Being human in public also makes you a better defender, because you understand the math of trust, the currency of favours, and the cheap tricks that work. That’s the ethical path: learn charm to defend, not to con.

If you’re a pen-tester reading this for fun, and dreaming of Sneakers-style capers, remember the constraints: ethics, legality, and the serious consequences of deception. Real engagements require signed scopes, transparent executive buy-in, and after-action coaching that respects people. The target of a test is the organisation, not the individual. A good report doesn’t point fingers; it shows the path an attacker took and gives a sequenced roadmap to stop them. If you can’t write that roadmap, you haven’t finished the job.

One more practical rumination for defenders: assume lateral movement. An attacker who gets past reception will try to move sideways. Compartmentalise networks, segregate credentials, and ensure that physical access does not equal administrative access. Train staff to treat unusual requests as normal and suspicious requests as normal too; normality, in security work, is the enemy of surprise. The theatre of a caper is entertaining because it compresses risk into a single sticky moment; real security is boring and slow because it’s built for the long haul.

The cultural part of this puzzle, how we teach, how we recruit, how we present the job, matters. Robert Redford’s screen charm made the caper palatable; his legacy through Sundance made storytelling a communal contract. For the cyber community, the takeaway is this: teach with stories, not slides. Tell the hotel scene from Sneakers in your training sessions and then walk through the policies that let it happen. Show someone the social engineering playbook and then give them the exact one-line script they can use to check a delivery. That’s how you turn cinematic mischief into institutional resilience.

So raise a glass to Bishop’s wit, to the team’s choreography, and to Robert Redford’s ability to make moral ambiguity look like a style choice. His charm was not confined to one genre; All the President’s Men nudged more than a few young dreamers into journalism, just as Sneakers nudged others toward cybersecurity. That’s the mark of a true titan of cinema: shaping whole careers with a performance, making craft and conviction look irresistible. He will be missed. And then, the very next morning, walk to reception and ask whether they’ve updated their visitor log. Gratitude and habit: the two most underrated defences.